Homebrewer’s Hideaway: How to Homebrew a World

Welcome to the first in our series on homebrewing! In these articles, we’ll cover off worldbuilding, making items, designing stories, and developing spells, characters, and everything else you could possibly want to create yourself.

Homebrewing is both challenging and rewarding, and there are always a number of factors you’ll want to account for.

How do I create a world?

Trying to come up with a whole world from scratch can be pretty daunting. Your players will have adventures here, and players are known for ripping holes in things you didn’t even know you needed to create.

It’s impossible to conceive an entire world as a single idea. Nothing is born all at once – it’s a step-by-step process that you can actually break down.

1. Develop a single idea

Every world has to start somewhere. Find one defining idea that you like as a base. It should be broad and sweeping, like “water is very scarce”, or “everyone can use magic”.

That idea will help inform the rest of your world.

2. Build outwards from your idea

Once you have a single idea, you can use that as a set of logic dominos.

Let’s use the example of “water is scarce”. Once you know that, you already have a rough idea of what the world might look like – there’ll be a lot of desert, and maybe some savannah-like areas.

You might also suggest a reason why water is scarce. Perhaps it’s hot because the sun never sets, or maybe it’s incredibly cold because all the water is frozen in ice deep below the surface, making it inaccessible.

Both offer new ideas that come off of them: heat means people will dress in lighter fabrics, while cold means they’ll wrap up warm. That’ll change how people look and act, and how they travel and gather.

If all the water is deep below the surface, maybe people mine it out. That makes ice a commodity. If water scarcely exists at all because of the heat, maybe people and animals have taken to drinking different fluids – maybe even blood.

The key here is, for every idea you see, follow it back a step or forward a step. Why is that idea the case? And what does it mean for the people who live there?

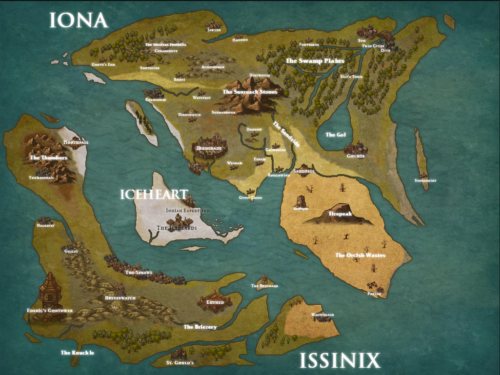

3. Make a map

While it’s not necessary to make a map to have a clear idea of a world, it can be really helpful for determining the political state of things.

You might already know from step 2 that with water as rare as it is, people consider it valuable enough to fight over. But who’s doing the fighting? And where are the resources they’re fighting for?

A system like Inkarnate or Wonderdraft can help you lay out your thoughts in a clear order.

But making a map is more than just slapping things down where they look cool. There are a few things you should remember when placing map features:

- Water always flows downhill (or not at all, in our example!) and only bends because of a changing incline or because of an obstacle.

- Coasts exposed to the sea will gradually erode, meaning any outcroppings are likely to turn into islands or be worn away altogether.

- Mountains tend to occur as ranges rather than individual peaks. Though if you want to throw Mount Doom in there, do your thing!

- Towns and cities spring up in places where there’s a natural resource (if it’s, say, starting as a mining town), where the spot is defensible (if locals are prone to fighting), or where there’s a lot of through-traffic (as traders need a place to stay).

These are only a handful of map-making tips, but just by remembering those, your map is likely to become much more believable and lend itself to the next step.

4. Build out history

While step 2 gave us the general reasons why the land is the way it is, and 3 told us where these things take place, this step helps to set your stories in context.

If you already know that water is scarce, and you now know that there’s a water mining town not far from a defensible one, it’s easy to believe that the latter might have either had trade deals with the former – or attacked it for its resources.

The best way to grow your history is by repeating step 2 but while looking at your map. Consider these:

- Most locations will naturally develop a ruling faction, whether a monarch or a council of some sort. They will focus on retaining their power, which means securing sufficient resources for their people.

- Leaders who fail to secure resources for their people will prompt revolutions, small or large.

- Securing resources might be through trade, but certainly in early days of civilisation it’s much more likely to be through warfare. They’ll attack other settlements nearby and raid them or capture them, forming small empires or kingdoms.

- When towns are small, there aren’t likely to be many factions there. Once they reach city size, however, there’s more power to be gained, and different groups will form trying to size their corner. This is often a good origin for guilds, if you’re interested in that fantasy staple.

Again, there are lots more points to consider, but this can help lay out some of the political landscape of your world.

5. Play the adventure

It’s possible to run through these steps forever, endlessly developing more and more of your world. But usually there’ll be something you haven’t thought of. Your players will.

By running an adventure in the world you might find out about all sorts of ludicrous concepts like local taxes or urban myths that don’t generally get included when building the setting from scratch.

Once you have enough of a world that you can start writing quests in it, you probably have enough to get going with a campaign or one shots!

Leave a reply